Amy Winehouse

The death of Amy Winehouse in 2011 was tragic of course; there is no “but.” It was tragic in ways that perhaps many people don’t understand. This may be because they weren’t into her music or didn’t follow her career – because those two things are not identical. If Amy showed us anything it is that her music and her public self weren’t the same though they came close to converging upon the release of Back to Black in 2006.

Amy’s tragedy was twofold: firstly, it was her descent into what Elton John apparently warned John Mayer about: “the world of bullshit.” Amy was not best suited to it; she was troubled from a young age anyway and I suspect the level of talent on which she operated didn’t render her especially amenable either to what the rest of us know as ordinary life. She said herself she feared fame and defined success not in terms of money or exposure but rather the freedom to record her music as she saw fit.

Her fame exploded when her troubled life became more interesting to the public than the music. This perversity is encapsulated perfectly in the song that made her a household name: Rehab. She had finally conformed to the dreaded rock ‘n’roll stereotype: she was skinny and had that “heroin chic” appeal – she looked like a drug addict; she had a destructive relationship with a drug-addicted boyfriend, later husband, Blake Fielder-Civil; she had that so-called “difficult relationship with the press” that people find so alluring; she was over-exposed, on TV all the time, “in the news,” a commodity.

Her first manager, Nick Shymansky perceived that a time came when the world wanted a piece of her. He’d seen the signs of her possible self-destruction early on. His association with Amy began when she was sixteen and he was nineteen; they were pretty clueless but were figuring it out together. He seems to have been her friend, manager, minder and brotherly-influence all at once. This was when fame was only a notion, when the music was firmly at the centre of things – music and fun and adventure.

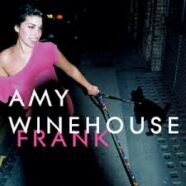

The second way in which her death was tragic is this: unlike Springsteen or U2, Amy will always now be who she was just when she had reached a wide audience; there won’t be time or space for her to reflect on it and explain it through song, to remove herself from that “moment” she got stuck in. She went to her grave without an opportunity to shed all that garbage she embraced and that others foisted on her. There won’t be any further explanation of how she lost the reins. To experience the best of her you have to go backwards, to Frank.

Yet, Frank is a far superior album to Back to Black (and the latter is a pretty good album.) But the comparisons help explain what fame can do to an artist. While Frank is full of songs of immense emotional intensity, creative playfulness and subtlety, Back to Black is catchy yet crass, sometimes bland and amorphous. It yielded five hit singles; Frank was by comparison more like a cult phenomenon. Amy met Blake in a pub between the albums; their ill-fated meeting and subsequent highly-publicised relationship and drug consumption took her away from the girl who recorded and catapulted her to stardom from where she never returned; quite the contrary, it ate her up and she fed herself to it. If Blake is to be believed, Amy found it difficult to access her feelings. It’s hard to believe when you listen to the songs. But isn’t that just it: her songs were her salvation and ironically fame separated her from them and it’s starts to happen on Back to Black.

On You Sent Me Flying (in which she pronounces kicked ‘kick-ed,’ adding a syllable, something she does only once) she writes about songwriting: “It serves to condition me/ And smoothen my kinks/ Despite my frustration for the way that he thinks.” Her songs were her means of regulating the world; fame disrupting that gift she’d given herself because fame didn’t care for her self-control; it’s not a random fact that Rehab was her first major hit; the idea of a young wild thing refusing to stop drinking and getting high caught the public imagination because she appeared to conform to what a rock star was meant to be like. Rehab lacks all the subtlety and verve of other songs: “They tried to make me go to rehab/ I said ‘No, no, no!” Compare it to Stronger than Me: “You should be stronger than me;/ You’ve been here seven years longer than me/ Don’t you know you’re s’post to be the man;/ Not pale in comparison to who you think I am.” The one is Amy as stubborn, live-fast-die-young hell-raiser, the latter a sophisticated and frustrated lover.

There was so much more in Amy one suspects – or there would have been had she been been able to sustain the beautiful discipline of the songs on Frank instead of embracing the marketability and attractive despair of Back to Black. At least in her young life she did something that will never I imagine be forgotten; in the future people will discover her through Back to Black and then they’ll suspect there was more to her and they’ll find it on Frank and that’s when they’ll fall in love with her.

R.H.