Dangerous politicians, Orwell and more

One of the books I got recently is James Gilligan’s Why Some Politicians are more Dangerous than Others. He’s a psychiatrist and was trying to work out why there are periodic spikes and dips in lethal violence in The United States. He was able to use data to demonstrate that there’s a direct correlation between Republican presidents and rises in lethal violence and falls during the tenures of Democratic presidents. He tells us on page 3 that “When [he] subjected these yearly changes to statistical analysis, [he] found that in all three cases – for suicide, for homicide, and for total lethal violence (meaning suicide and homicide rates combined) – the association between political party and lethal violence rates was statistically significant.” What’s more, the data shows that murders and suicides rise and fall together which is remarkable because, as Gilligan rightly says, we don’t see suicides (the people that is) as being very similar to murderers. Suicidal people “are generally considered to be either sad or mad; they are patients usually seen in a psychiatric office or hospital. People who commit homicide are usually seen as criminals and considered to be bad. They are commonly regarded as needing not treatment but punishment, and they are found, for the most part, in prison, not mental hospitals or private offices.”

On the subject of motivation for murder and suicide, Gilligan argues that “shame [is] the proximal cause of violence, the necessary – although not sufficient – motive for violent behaviour.” He wonders whether “unemployment, relative poverty, and the sudden loss of social and economic status have been observed to increase the intensity of the emotion of shame.”

Orwell on Nationalism

Then I turn to George Orwell’s essay, Notes on Nationalism. He writes that this is “the habit of assuming that human beings can be classified like insects and that whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled ‘good’ or ‘bad’. But secondly – and this is much more important (my emphasis) – I mean the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil and recognizing [sic] no other duty than that of advancing its interests.

“Nationalism,” Orwell goes on, “is not to be confused with patriotism.Both words are normally used in so vague a way that any definition is liable to be challenged, but one must draw a distinction between them, since two different and even opposing ideas are involved.

| Orwell on Patriotism | Orwell on Nationalism |

| By ‘patriotism’ I mean devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force upon other people. Patriotism is of its nature defensive, both militarily and culturally. | Nationalism’ on the other hand, is inseparable from the desire for power. The abiding purpose of every nationalist is to secure more power and more prestige, not for himself but for the nation or other unit in which he has chosen to sink his own individuality. |

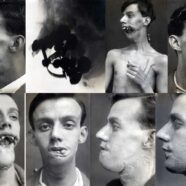

Les Poilus

Les poilus were the French soldiers of World War I. The term translates as “the hairy ones” and it was ascribed because the men didn’t get many opportunities to shave. I first came across the word in Niall Ferguson’s The War of the World and I Googled it and found an item on France 24 in which a reporter, Florence Villeminot, explains the term and others too such as gueules cassées which means “the broken faces,” gueule being slang for face, presumably equivalent to the English “mug” or “puss.” These poor guys weren’t eligible for compensation because they were able to work, could stand and walk and lift and so on. However, they walked about the street and scared people and were ostracised. The news report features the testimony of a man whose own face appears ravaged by war injury called Henry Denys de Bonnaventure who shows pictures of the kinds of injuries to men’s faces that weren’t considered serious of debilitating enough to warrant some state intervention. But they got a kind of revenge because their association invented the French lottery and they still get a cut of its takings to this day. Villeminot goes on to remind us that Macron got in trouble over comments to the effect that Petain should be honoured even though he was an arch collaborator during the war and facilitated the Nazi regime’s crimes. She finishes by answering the question she says she’s often asked: Do the French wear the Poppy symbol like the British? The answer is no: they do wear Le Bleuet though, sales of which fund charities for those French who die in war and are victims of terrorism.

Stuff about China

A review (25-26 January) in the FT Weekend of two books, Just Hierarchy: Why Social Hierarchies Matter in China and the Rest of the World by Daniel Bell and Pei Wang and Against Political Equality: The Confucian Case by Tongdong Bai adverts to a debate in and about China. On the one hand is the western-style individualistic rights of action and expression familiar to a lot of us in this part of the world and the ethical, moral, Confucian-type behaviour Chinese people are probably more attuned to. The two books make the case for hierarchies being good for a country because they can strengthen and stabilise a nation. Equality, in a word, is overrated. Bell and Wang argued that meritocracy “as seen within the Chinese Community Party (CCP) in its ideal form, can be superior to electoral democracy.” They try to sell to their readers the cultural value of hierarchy in Asian societies. This applies to AI for instance. The Silicon Valley, Western approach is to allow the car to learn its owner’s preferences while the Asian equivalent would take into account limitations that might serve the community better such as collective ownership and programming to prevent speeding so as to allow constant flow of traffic. AI, in other words, “will have to be culturally inflected in other societies by norms that may be very different from those of the US. This is an important debate that is only in its early stages.”